Many of you have requested deeper-dives into the artists that I feature, as the account - despite originally conceptualized as a vehicle for entertainment - has also come to function as an educational tool; exposing folks to new art/artists, and fostering an appreciation that many never knew they had in them. Aggregating information that’s available online (such as Wikipedia) into a digestible format will serve as the foundation, but I also want to bring something unique to the table, which is why each of these will be interlaced with perspective from an expert on the subject.

I figured it’d be fitting to do my first one of these on an artist that I only learned about since starting the account, Clyfford Still. We’ll be accompanied on our journey by Missy Brown, a Museum Educator at the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver, Colorado. A former public school teacher with a BFA in photography and a concentration in art education, Missy is involved in the museum’s diverse set of programming and has worked there since August, 2022.

Life

Born in 1904, Clyfford Still was well-educated, with various academic studies culminating in a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1935 from Washington State College (now Washington State University), where he also taught until 1941. He had his first solo exhibition in 1943, and in 1946 began teaching at the California School of Fine Arts (now San Francisco Art Institute). It was then that Still began developing the style that would come to define his work. From Wikipedia: Still’s non-figurative paintings are non-objective, and largely concerned with juxtaposing different colors and surfaces in a variety of formations. Unlike Mark Rothko or Barnett Newman, who organized their colors in a relatively simple way (Rothko in the form of nebulous rectangles, Newman in thin lines on vast fields of color), Still's arrangements are less regular.”

In 1950, Still relocated to New York City. It was the height of Abstract Expressionism; artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning were names that came to define the era. It was also around this time that Still became increasingly critical of the traditional art world, severing ties with commercial galleries and moving to a 22-acre farm in Maryland. He continued to work in the state (moving to New Windsor in 1966) until his death in 1980, largely removed public eye.

Many people, even those with art history backgrounds, including Missy, grew up without ever hearing about Still, despite a catalog of work that positioned him as one of the foremost figures in Abstract Expressionism. Part of this was due to his separation from the art world, but also because in 1978, Still wrote a will that dictated: "I give and bequeath all the remaining works of art executed by me in my collection to an American city that will agree to build or assign and maintain permanent quarters exclusively for these works of art and assure their physical survival with the explicit requirement that none of these works of art will be sold, given, or exchanged but are to be retained in the place described above exclusively assigned to them in perpetuity for exhibition and study." From Missy, “he wasn't really in the history books because from his death in 1980 to 2011, a large amount of his art was in storage, and no one from the public could look at it.”

Museum

In the years following Still’s death, several cities bid on his collection, including Denver, who, from Missy, “bid on it once and got denied because the proposal had it as a wing of the Denver Art Museum and the estate (based on his will) mandated that it had to be its own museum.” Denver, with a group headlined by Still’s widow Patricia Still, then revised the bid and won in 2004, in part because, according to Missy, “(Clyfford) didn't like the coasts because to him they represented the traditional art world, and Denver was pitched as a pioneering city.” The museum opened in 2011, and has 93% of Still’s work. “We know that,” says Missy, “because he documented everything he ever made, and so we know for example that there are several works that are lost. The collection includes slides, prints, works on paper, paintings, and even some sculptures.” While a handful was sold to help fund the endowment, a large majority of the works are housed at the Clyfford Still Museum, which now features a collection of approximately 2,500 pieces, and serves as a single-artist museum.

Programming there ranges from toddlers all the way to older adults with memory loss. From Missy, “We have a really unique experience and I think young children are actually really connected to abstract art and have a unique opinion and experience with it. We had an exhibition called Clyfford Still, Art, and the Young Mind for children ages zero to eight. And they’re the ones who ‘get it’ immediately. You don't have to explain it, and they appreciate the scale of his work the most, because it’s twice as big in their eyes. And for the older people with memory loss, I think abstract art plays a special role in helping to keep them sharp, as it requires deeper interpretation.”

My Experience with Still

In November of 2020, I went to the MoMA, and saw Painting 1944-N No. 2 for the first time, one of the few pieces of Still’s that lives outside of the museum. Dynamism through contrast on an 8' 8 1/4" x 7' 3 1/4" canvas, it’s a work that’s hard not to be captivated by.

From Missy: “Still really didn't tell anyone what his paintings meant, and was known to ask inquiring minds ‘well, what does it mean to you?’ They would go on a long explanation of what they saw and then he would say, ‘that tells you a lot about me, or tells me a lot about you,’ and then walk away. He was very hands off and wasn’t interested in dictating to people what they were supposed to get out of his work.”

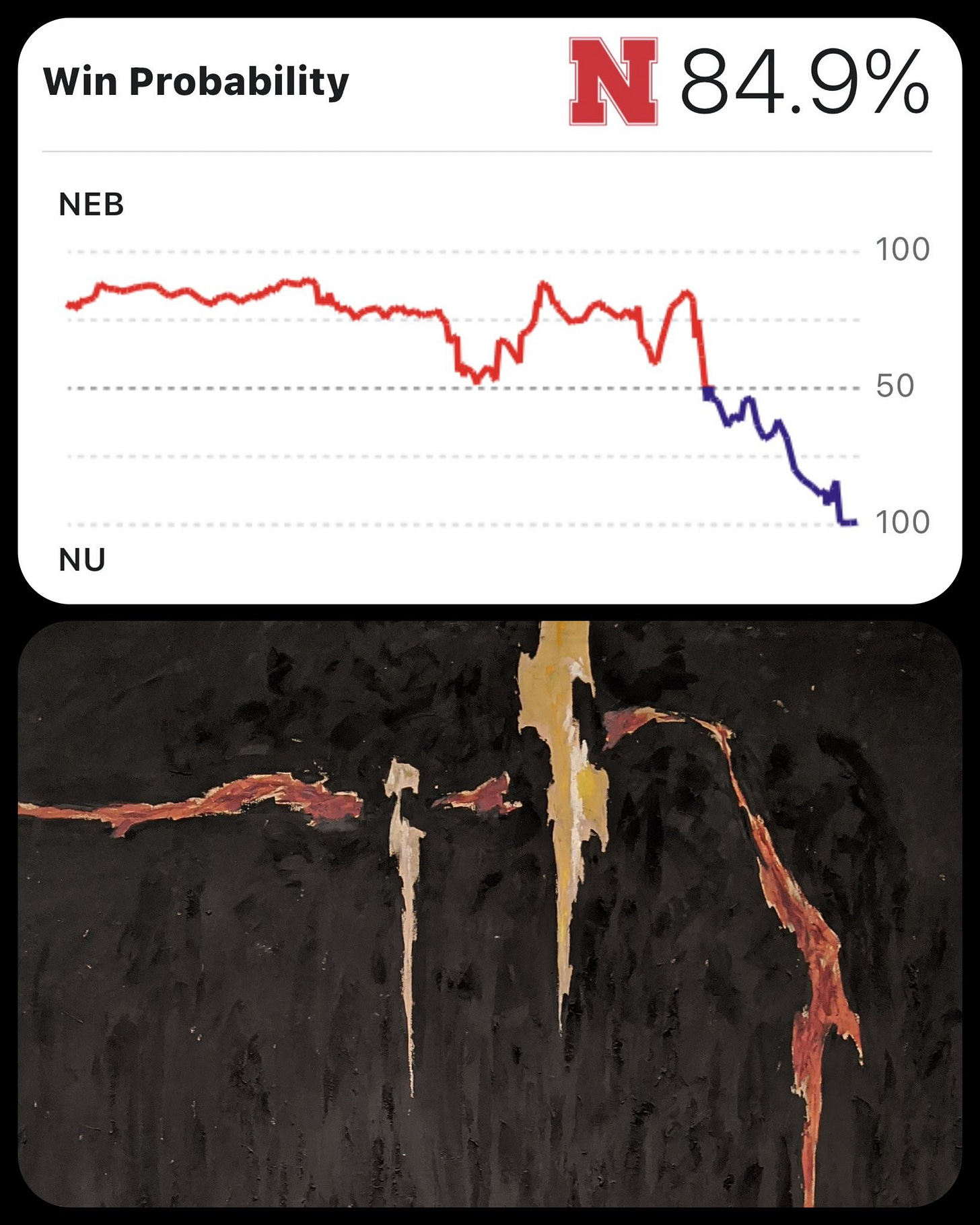

For me personally, when I see this particular work, I’m reminded of win probability charts where a team is humming along, only to shit the bed in dramatic fashion at the end and fall off a cliff: otherwise known as Nebraska Football.

I also tend to gravitate towards his work when I see sports images that have ‘movement in color’ or call for something more abstract. For example, with this angle of the Mahomes below, you’re likely not going to see someone missing a part of their helmet in art history (the closest I could think of was the Extraction of the Stone of Madness), and I figured that Still might have something contrasting red and black with a shape that could mimic the missing area.

From Missy: “He was kind of a character and we're always coming across interesting stories. One funny one is he sold/gave a painting to someone and then decided that he shouldn't have it anymore. And so he broke into the guy's house and cut a whole square out of the middle of the painting because then it wouldn't be worth anything. And then he had a falling out with (Mark) Rothko towards the end of his life, and in a letter he wrote that after he had cut that square out, it was akin to one of Rothko’s works.” I don’t necessarily know how to explain it, but I can feel that story through his paintings, as he somehow captures both youthful rebelliousness with a mature, defined seriousness. It’s why when anything whimsical comes up that somehow also requires a finer attention to detail - like the Mahomes or the Jordan dunk - it puts me in a Still frame of mind. Also, he was apparently a big fan of baseball, so I’m hoping something happens this season that evokes his work. Huge thanks to Missy for her incredible insight & time - if you’re in Denver, go visit her and the Still collection at the museum!

Two More Still Memes for Paid Subscribers: